Jadual Kandungan

Beri-Beri di Tanah Melayu (1848-1910)

Dirujuk oleh

Kronologi

1848: Rekod Terawal Penularan Wabak

Penularan wabak beri-beri secara berleluasa di Tanah Melayu kali pertama direkodkan pada tahun 1848. Di antara tahun 1886 hingga 1901, puluhan ribu korban wabak ini, kebanyakannya di kalangan pekerja asing di ladang-ladang, telah direkodkan di Sumatera, Tanah Melayu, dan Singapura, antaranya oleh Dr. A.W. Sinclair (State Surgeon Selangor 1882-1888) dan Dr. William Leonard (W.L.) Braddon, District Surgeon Selangor ketika itu: “A severe outbreak of beriberi in Malaya was first observed in 1848. Two decades earlier, Bankier, a naval surgeon in India, had listed the symptoms of the disease to include paralysis of the muscular and nervous system, chest pain, spinal cord problems, chronic cough, kidney failure, water retention, fever, and bowel conditions. British colonial reports issued between 1886 and 1901 noted tens of thousands of deaths in Sumatra, Malaya and Singapore during that time. These included reports from Dr A. W. Sinclair, who served as the Selangor State surgeon from 1882-1888, and Dr Leonard Braddon serving in that state as District Surgeon. Both reported a particularly heavy toll amongst foreign workers, known as coolies, largely brought in to work on the colonies’ plantations, where they were supplied with food as cheaply as possible.” (Nia Deliana @ Inside Indonesia, Sep 15, 2022: |"Chasing a cure for beriberi").

1875-05: Rekod Rasmi Wabak Beri-Beri

Antara rekod rasmi yang terawal berkenaan penularan wabak beri-beri di Tanah Melayu, kebanyakannya di kalangan para banduan penjara, pada bulan Mei tahun 1875: “Bermula tahun 1790 hingga tahun 1857, sebanyak 20,000 banduan dibawa masuk ke NNS (Negeri-Negeri Selat). NNS menjadi jajahan British yang telah menerima banduan paling ramai berbanding wilayah kolonial yang lain. Selain menerima kemasukan banduan, banduan dari penjara-penjara NNS turut dihantar keluar ke Penjara India. Ini kerana pusat pentadbiran British di Asia ketika itu adalah di jajahan kolonial India. Namun sejak penubuhan dan perkembangan penjara di NNS, terdapat satu penyakit misteri yang telah menyerang keseluruhan populasi penjara. Ia melibatkan sebahagian jumlah banduan yang mana sebanyak 25% daripada jumlah keseluruhan populasi banduan mati kerana penyakit ini. Antara gejala penyakit yang ditunjukkan adalah seperti keadaan lesu (lassitude), bengkak (oedema), kebas kaki dan tangan, kehilangan selera makan, masalah penghadaman, dan gangguan sistem saraf. Manakala bagi banduan yang berada pada tahap kronik menunjukkan gejala lumpuh, masalah sistem jantung, diikuti dengan restlessness (kegelisahan) dan akhirnya meninggal dunia. … Beri-beri yang paling awal direkodkan di Penjara Negeri-Negeri Selat adalah pada bulan Mei tahun 1875. Sejak awal direkodkan, kebanyakan laporan di penjara mengklasifikasikan penyakit beri-beri ini sebagai penyakit berjangkit. Ini kerana penyakit ini menular dengan kadar yang sangat pantas dan tidak diketahui status penyakit yang sebenar. Pada tahun 1877, ia mula dikelaskan secara rasmi sebagai satu penyakit khusus iaitu penyakit beri-beri. Hakikatnya, sebelum diumumkan sebagai penyakit beri-beri pada tahun 1875, terdapat jumlah kemasukan yang tinggi direkodkan. Sebagai contoh, dapat dilihat dalam tahun 1870, terdapat 1981 kemasukan banduan ke hospital, tahun 1871 sebanyak 1933 kes, kemudiannya meningkat tahun 1873 kepada 2500 kes. Pada tahun 1874, jumlah kes beri-beri di Penjara NNS masih berlaku secara konsisten.” (Siti Alwaliyah, Ahmad Kamal Ariffin Mohd Rus @ Jebat: Malaysian Journal of History, Politics & Strategic Studies, Vol. 46 (1) (July 2019): 27-57: |"Penularan penyakit beri-beri di penjara Negeri-Negeri Selat: penelitian terhadap sebab dan langkah-langkah kawalannya, 1870-1915", m.s.32).

1880-1900: Penularan Berleluasa

Wabak Beri-Beri mula menular dengan berleluasa pada suku akhir kurun ke-19, dan kebanyakan penghidapnya adalah imigran Cina. Sepanjang waktu itu, puncanya tidak dapat dikenalpasti: “Beri-beri began spreading like wildfire throughout Malaya during the last quarter of the 19th century. It was particularly prevalent among young Chinese immigrants and, at that time, nobody had any clue of its origin.” (Alan Teh Leam Seng @ New Straits Times, June 16 2021: |"Malaya led the way in medical research").

“Penularan di Perak pada tahun 1879 merupakan rekod paling awal yang mendedahkan serangan penyakit beri-beri di Tanah Melayu. Penyakit ini mengakibatkan kematian yang tinggi dalam kalangan banduan di Penjara Taiping iaitu sebanyak 25 peratus daripada jumlah keseluruhan banduan. Sebelum pembentukan Negeri-negeri Melayu Bersekutu pada tahun 1896, sebanyak 59,080 kes beri-beri dengan 8,270 kematian direkodkan di Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan dan Pahang antara tahun 1883 hingga 1895 menjadikan penyakit ini sebagai penyakit yang paling utama menyerang penduduk di negeri-negeri tersebut. Antara 1896 hingga 1914 pula, penyakit beri-beri kekal sebagai salah satu penyakit utama di Negeri-negeri Melayu Bersekutu dengan Perak dan Selangor menjadi negeri sasaran utama penyakit ini. Hal ini dapat dibuktikan melalui jumlah kes beri-beri yang dirawat iaitu sebanyak 141,579 dengan 20,754 kematian. Penyakit beri-beri mendatangkan keresahan kepada British kerana ia memberi kesan yang amat besar dari segi guna tenaga buruh. Pelan tindakan pengawalan penyakit beri-beri mula dibentuk bagi membendung penularannya yang semakin serius.” (Noraini Mohamed Hassan @ Sumbu Dunia Melayu: Hubungan Keserumpunan Malaysia-Indonesia, 2017: "Penyelidikan Beri-Beri di Tanah Melayu dan Hindia Belanda, 1880-an Hingga 1914, m.s.274).

“Between 1885 and 1905, according to Dr WL Braddon, over 150,000 sufferers from beri-beri were treated in government hospitals in Malaya. He estimated that 30,000 died, while many who recovered were permanently disabled from the disease. Malaria killed more, usually after a fairly short febrile illness. Beri-beri however, landed many weak and ill in hospitals. Beri-beri patients also died, but not as quickly. They were rendered miserable wretches, unable to work and care for themselves.” (Lim Kean Ghee, 2016: |"THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH IN MALAYSIA", m.s.53).

Punca penyakit ini tidak dapat diketahui, dirumitkan pula dengan keadaan hidup pekerja asing yang serba daif dan bermasalah, yang menyukarkan pencarian puncanya: “Unclear diagnosis was prevalent due to the range of symptoms in common with other endemic diseases, and its causes remained largely a mystery throughout the nineteenth century. In Malaya, the British middle class strongly believed that the origins of the disease stemmed from within the unhygienic and illiterate native populations, and so the medical measures taken were highly racialised. Medical inspections, treatments, and curfews were centered on the dwellings of the native populations only.” (Nia Deliana @ Inside Indonesia, Sep 15, 2022: |"Chasing a cure for beriberi").

Walaupun punca spesifik setiap wabak hanya diketahui berpuluh tahun selepas penularannya, puncanya secara umum ialah penyahhutanan besar-besaran untuk tujuan pembukaan kawasan ladang dan perlombongan yang besar, serta jaringan jalan-jalan pengangkutannya, yang mengakibatkan ketidakseimbangan ekologi dan penularan wabak. Pekerja migran yang dibawa masuk oleh pihak British pula tidak mempunyai daya ketahanan semulajadi terhadap wabak tempatan. Pakar serta kakitangan perubatan British pula, kurang berpengalaman dan berpengetahuan mengenai wabak-wabak tersebut, lalu mengakibatkan puluhan ribu pekerja terkorban olehnya: “…jangkamasa 1896-1914 merupakan tempoh yang paling penting untuk memahami peranan British dalam mengawal penularan penyakit ekoran eksploitasi ekonomi yang dialami oleh negeri Melayu di bawah pentadbiran British. Menurut J. Norman Parmer, “British rule first made the incidence of disease and death very much worse than before. The clearing of land for estates, the expansion of mining and the construction of public works disturbed existing ecological balances, causing diseases to spread and multiply. The large immigrant labour forces assembled for these capital investments lacked natural immune systems. The colonial government, the chief provider of medical services, also lacked experience and knowledge and as a consequence many tens of thousands of workers died.”” (Noraini Mohamed Hassan, 2004: |"Penyakit tropika di Negeri-Negeri Melayu Bersekutu, 1896-1914 : tumpuan kepada penyakit beri-beri, malaria dan penyakit usus", BAB SATU: PENGENALAN).

1900-02: Penubuhan Institute for Medical Research (I.M.R.)

Institute for Medical Research (I.M.R.) ditubuhkan pada tahun 1900 di Kuala Lumpur, bagi mengkaji punca dan tatacara kawalan wabak Beri Beri dan lain-lain. Pengarah pertamanya ialah Dr. Hamilton Wright: “There were many theories about the cause and nature of the disease, and in 1900 the worried British authorities established the Institute of Medical Research in Kuala Lumpur with the aim of solving the mystery of beriberi and other diseases … Dr. Hamilton Wright, the first Director of the Institute of Medical Research, wrote to Sir Patrick Manson about the cause of beriberi and assured him that they were 'sure to find the organism soon” (Enid Wylie, 1988: |"THE SEARCH FOR THE CAUSE OF BERIBERI IN THE MALAY PENINSULA", m.s 3-4).

“Prolonged periods of sustained and efficient research took root soon after February 1900, when the resident-general founded the Pathological Institute in Kuala Lumpur. This laboratory, which later became known as the IMR, began initiating plans to prevent and cure highly lethal scourges that were the bane of many Malayans.” (Alan Teh Leam Seng @ New Straits Times, June 16 2021: |"Malaya led the way in medical research").

“The Institute for Medical Research (IMR) began with a recommendation in 1900 from Sir Frank Athelstane Swettenham, the Resident-General of the Federated Malay States, to establish a Pathological Institute in Malaya to “carry out scientific and sustained research into the causes, treatment and prevention of such scourges as beri-beri and all forms of malaria fevers”. This proposal was made following the resolution of the Conference of Berlin held in Europe in 1885 to undertake such activities so as “to promote the moral and material well-being of the native population and to explore the great and unknown field of tropical medicine”. The European colonial powers at that time namely the French, Dutch and English, moved almost simultaneously to establish new research institutions in the Colonies. The Pathological Institute in British Malaya was one such institution. It was to serve as a research outpost for the London School of Tropical Medicine, established a year earlier in 1899 at about the same time as that of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. Kuala Lumpur was chosen as the site for the new Institute because of its central position in the Malay Peninsula. The time was opportune as the country was beset by not only tropical diseases such as beri-beri and malaria, but also by dysentery, small pox, cholera, plague, rabies and other endemic, sporadic, infectious and contagious diseases. Sir Patrick Manson, who was the Medical Advisor through the British Colonial Office at that time, appointed Dr. Hamilton Wright, a pathologist at the London School of Tropical Medicine, to serve as the Institute's First Director. Much of Wright's time during the first year was taken up with the planning of the new Institute. When the buildings were completed, a formal opening ceremony was held in February 1901 and in August of the same year, the Pathological Institute became known as the Institute for Medical Research.” (Institute for Medical Research (IMR), 7 August 2016: |"History").

1899-1907: Peranan Dr. W.L. Braddon

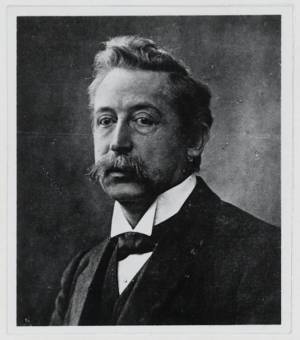

LATAR PERISTIWA: Dr. William Leonard (W.L.) Braddon (1862-1936).

1899-1901: Kajian Awal

Sebagai State Surgeon Negeri Sembilan, Dr. William Leonard (W.L.) Braddon menghadapi wabak beri-beri yang menular di sana. Pada mulanya beliau mendirikan pusat pemulihan pesakit beri-beri di tepi pantai Port Dickson, dengan sangkaan udara segar di sana dapat membantu, namun jangkaannya meleset. Menjelang tahun 1899, beliau diberi geran untuk mendirikan makmal kajian terhadap pesakit beri-beri. Berdasarkan dapatan kajian, beliau membuat kesimpulan bahawa penyakit tersebut tidak disebabkan oleh bakteria: “Braddon did much to treat beri-beri as well as to find out its cause. He established a sanatorium for beri-beri patients near Port Dickson. However, his faith in a seaside cure and an infection theory evaporated with the statistics from the sanatorium. By 1899, with a modest government grant, he set up a small laboratory and conducted over 80 experiments based on blood and tissues from beri-beri patients and healthy controls that, to him, ruled out bacteria as a cause of the disease.” (Lim Kean Ghee, 2016: |"THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH IN MALAYSIA", m.s.53).

Ternyata hasil kajian yang lebih ampuh adalah melalui pemerhatian di lapangan, khususnya di lombong Eropah di Jelebu. Beliau mendapati pekerja kontrak yang baru cenderung menghidapi beri-beri tahap serius, berbanding pekerja lama yang telah “bebas”. Antara perbezaan ketara dalam kehidupan mereka ialah pekerja bebas menyediakan makanan sendiri (biasanya berdasarkan beras tempatan / tradisi), manakala pekerja kontrak diberi makan beras kilang (biasanya diimport) oleh kontraktor mereka. Maka Dr. Braddon mengarahkan permakanan pekerja kontrak dipelbagaikan, dan dipindahkan dari rumah kongsi mereka. Hasilnya menggalakkan, dan menjelang tahun 1901, beliau telah menerbitkan hipotesis bahawa punca beri-beri ialah beras kilang, dan kesannya dapat dilihat di penjara Seremban selepasnya. “However, it was his observations at a European mine in Jelebu that confirmed for him what he suspected. Old hands, free men or ‘laukhek’ catered their own food, which included a varied diet and local parboiled rice, whereas ‘sinkhek’ were supplied imported polished rice by a local contractor. The ‘laukhek’ did not suffer from beri- beri as much as the ‘sinkhek’. On his advice ‘sinkhek’ were put on a more varied diet, but he also recommended that they be re-located. Beri-beri among the ‘sinkhek’ disappeared, but because of the re-location this event did not prove his theory. But by 1901, he had submitted his assertions that polished rice caused beri-beri, whereas parboiled rice did not and recommended that parboiled rice replace polished rice. In the Seremban prison, the benefits of this change were seen immediately.” (Lim Kean Ghee, 2016: |"THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH IN MALAYSIA", m.s.53-54).

Selain itu, beliau juga mengenalpasti amalan dan sumber permakanan yang berbeza di kalangan bangsa-bangsa utama di Tanah Melayu ketika itu, yang dianggap turut menjadi faktor utama: “Braddon had, in fact, made an important observation. The four ethnic populations had different dietary habits; the staple food of the Malays was rice, milled by hand in their own kitchens; the Tamils sieved out the bran after parboiling the rice; the Chinese consumed only white rice, imported, then milled by steam-driven machines and cleaned before it was sold; while most Europeans avoided rice altogether. It was the Chinese, Braddon concurred, who suffered seriously from beriberi, which he deduced, must therefore be due to some kind of toxin, perhaps fungal, that tended to accumulate in their rice during storage.” (Walter Gratzer, 2006: "Terrors of the Table: The curious history of nutrition", m.s. 141).

Namun “teori beras” ini menerima tentangan dari pakar-pakar serta pengurusan perubatan, oleh kerana teori yang lebih diterima umum ketika itu adalah berdasarkan jangkitan bakteria: “Dominasi teori jangkitan sebagai punca beri-beri bukanlah sesuatu yang menghairankan pada penghujung abad ke-19 berikutan penemuan oleh Louis Pasteur mengenai bakteria dan jangkitannya sebagai punca penyakit. Hal ini menjadikan bidang bakteriologi mencapai kedudukan yang tinggi dalam pendidikan perubatan sekaligus mempunyai pengaruh yang sangat kuat dalam kalangan ahli-ahli perubatan. … Beberapa tenaga perubatan menentang kuat hipotesis Dr. Braddon. Antaranya adalah Dr H.A. Haviland, District Surgeon, Parit Buntar Perak, Dr. Travers dan Dr.W. Gilmore Ellis, Superintendan Singapore Lunatic Asylum.” (Noraini Mohamed Hassan @ Sumbu Dunia Melayu: Hubungan Keserumpunan Malaysia-Indonesia, 2017: "Penyelidikan Beri-Beri di Tanah Melayu dan Hindia Belanda, 1880-an Hingga 1914, m.s.276, 278).

1902-1903: Wabak Beri-Beri di Penjara Pudu

Salah satu contoh perselisihan pendapat mengenai punca wabak beri-beri di antara Dr. Braddon dengan tokoh-tokoh lain ketika itu ialah pada tahun 1902, yang melibatkan State Surgeon Selangor Dr. Ernest Aston Otho (E.A.O.) Travers. Ianya dicetuskan oleh permohonan lawatan Dr. Braddon ke Penjara Pudu di Kuala Lumpur, berikutan wabak beri-beri yang memuncak di sana, serta ketidakpuasan hati beliau terhadap laporan yang disediakan oleh Dr. Travers. Dr. Travers yang telah pun sedia cenderung menolak “teori beras” beliau itu, mengemukakan pertikaian terhadap tujuan lawatan tersebut. Malah Pengarah I.M.R. 1900-1903, Dr. Hamilton Wright, turut mengaitkan beri-beri dengan sejenis organisme, sekaligus menolak “teori beras” Dr. Braddon: “Dr. Hamilton Wright, Pengarah Institut Penyelidikan Perubatan Kuala Lumpur (1900-1903) dalam tulisan beliau yang bertajuk “Observations on Beri-beri in the Kuala Lumpur Gaol” contohnya, mengaitkan beri-beri dengan sejenis organisme.” (Noraini Mohamed Hassan @ Sumbu Dunia Melayu: Hubungan Keserumpunan Malaysia-Indonesia, 2017: "Penyelidikan Beri-Beri di Tanah Melayu dan Hindia Belanda, 1880-an Hingga 1914, m.s.275). Akhbar ketika itu turut menyiarkan bangkangan terhadap “teori beras” yang dikemukakan oleh Dr. Braddon: “The much vexed question of the causation of beri-beri by the consumption of bad rice is thus handled by for Traders in the Medical Report on Selangor for 1902. A comparison between the Tai Wa Ward and Leper Asylum, on the one hand, and the Pudoh Gaol on the other, affords a very convincing proof against the theory of the causation of beri-beri by a toxin contained in Rangoon rice. … In the Pudoh Gaol, Tai Wa Ward, and Leper Asylum, we have three institutions, the inhabitants of which are the same nationality. The Rangoon rice consumed by them is supplied from the same source. It would be reasonable to support that if the disastrous outbreak of beri-beri that occured in one of them, the Pudoh Goal, during the year, were conveyed by the Rangoon rice, the patients in the Tai Wa Ward and Leper Asylum should suffer from beri-beri in the same way as the prisoners. This has, however, not been the case;” (The Straits Times, 9 June 1903, Page 2: |"RICE AND BERI-BERI").

Petikan surat-menyurat berkaitan lawatan Dr. Braddon ke Penjara Pudu (1902-1903):-

15/10/1902: Dr. Travers: “I have the honour to inform you that from a statement made by Dr Braddon in connection with the experiments carried out by me at the Pudoh and Old Gaols in 1895-1896, I find that he has been in some way led to make a very serious misstatement on the subject. 2. The remark I refer to is the following - “Your Pudoh Gaol and Old Gaol experiment is vitiated by the fallacy that, all those who stayed and got Beri Beri at Pudoh were long sentenced prisoners, and all those at the Old Gaol short sentenced prisoners”. 3. The statement with regard to the prisoners who got Beri Beri at the Pudoh Gaol is easily and conclusively disproved by the Register of patients admitted to the Infirmary, the grade of the prisoner being given in every case. I find that of 269 prisoners admitted to the Infirmary, suffering from Beri-Beri between November 1st 1895 and June 30th 1896, 105 were short sentenced prisoners. The period covered by the experiment being from October 21st 1895 to July 1896. 4. The statement to the effect that all the prisoners sent ot the Old Gaol were short sentenced prisoners is absolutely incorrect. Prisoners of all grades were included among those temporarily transferred to the Old Gaol. - E.A.O. Travers, State Surgeon.” (15/10/1902: |"EXPERIMENTS, PUDOH AND OLD GAOLS, 1895-1896 MISSTATEMENT MADE BY F. BRADDON. LETTER TO RESIDENT GENERAL RE'").

22/04/1903: Dr. Braddon mencadangkan lawatan ke Penjara Pudu untuk menyelidiki rekod kes-kes Beri-Beri: “PROPOSAL FOR THE VISIT OF DR. BRADDON TO THE PUDOH GAOL IN ORDER TO INVESTIGATE THE RECORDS OF BERI-BERI CASES.”

27/04/1903: Dr. Travers: “Dr. Braddon's object in asking to be allowed to visit the Pudoh Gaol in order to investigate the records of Beri-Beri is an unusual one. In the course of an investigation on the subject of the Rice Theory of Beri-Beri of which theory Dr. Braddon is an ardent supporter, I have made a very careful examination of the Gaol records, going into every case, and with the assistance of the Gaoler, investigating the history of each prisoner attacked with Beri-Beri. The result has been very unfavourable to Dr. Braddon's theories, and has been dealt with fully in the enclosed memorandum published by me on the subject. Realising that our experience of Beri-Beri in the Pudoh Gaol has been entirely contrary to the theories which he supports, Dr. Braddon wishes apparently to dispute the reliability of our returns and to make investigations for himself.”

11/07/1903: Dr. Braddon: “The question of the cause of beri-beri, one of not only scientific but economic importance, is yet held by some to be obscure that it needs all the light which every enquiry can throw upon it. It was for the purpose of gleaning some information in connection with incubation - period of the disease, which the figures hitherto published from Pudoh do not show, that I asked permission to examine the records. … the figures which Dr Travers has quoted, enough for his purpose, are not enough for mine. They do not illustrate the points I particularly wish to elucidate. … I do very much wish to supplement the figures already published about Pudoh outbreak, by other (and in my humble opinion more important) figures which have not been made known. If Dr Travers could have furnished me with these statistics, I should have required nothing more.”

(Sumber: 22/04/1903: |"DR. BRADDON'S VISIT TO PUDOH GAOL").

1904: Pembentangan Awal Teori Beras

“In 1904, Braddon submitted a long draft manuscript on his findings and thesis to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, which impressed Patrick Manson. However, Manson did not think the evidence proved the case. Back in Malaya, Braddon faced resistance from both Wright and Daniels, the first two Directors of the IMR who were adherents to the germ theory.” (Lim Kean Ghee, 2016: |"THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH IN MALAYSIA", m.s.54).

“While on leave in Britain in 1904 Braddon sent his 537 page manuscript The Cause and Prevention of Beri-beri to the Secretary of State for the Colonies. … He claimed to have proved that the disease was 'a species of grain-intoxication' and 'what is more important, the means of preventing the disease are shown to be easy of application' (that is, by eating parboiled instead of polished rice). He urged the Government to give the work full publication and to implement 'the means of protection wherever the disease now occurs in countries under British Protection', … the paper was forwarded to Sir Patrick Manson for comment … Manson' s comments were favourable and the manuscript was returned to Braddon with the request that he make a precis of the work. Manson did not consider that Braddon had absolutely proved his theory but commented that he 'shows great industry and skill in the collection and interpretation of statistics and other matters relating to beri-beri. Braddon was gratified by Manson's reaction because, only two years before, Manson had announced that Travers' experiments in Pudoh gaol had 'proved up to the hilt' that neither rice nor any other kind of food had anything to do with beri-beri. Braddon had at least reopened the question as Manson recommended that Braddon be provided with the opportunity to carry out more experiments to prove his theory. … He argued that white polished rice (which he called 'uncured' rice as distinct from parboiled or 'cured' rice) became infected by an organism, 'probably a special fungus' which produced a toxin. He believed that this toxic substance which was produced by this special fungus poisoned those who ate it in large quantities. … He offered special thanks to Dr. E. A. O. Travers 'for much stimulating criticism in consistent opposition to the views expressed in the work and in Appendix I of the book he quoted the main part of Travers' report on his experiment carried out in Pudoh Gaol in Selangor during 1895 - 1896, but not published until 1902. It was this paper which had prompted Manson's statement that Travers had proved that beri-beri was not connected with diet. Braddon supplemented the paper with information gleaned from official reports made by Travers and his colleagues and interpreted the resulting information to refute Travers' proof that the incidence of beri-beri was not connected with diet.” (Enid Wylie, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. 61, No. 2 (255) (1988), pp. 93-122: |"THE SEARCH FOR THE CAUSE OF BERIBERI IN THE MALAY PENINSULA"), m.s. 9-17).

1905-1908: Pembuktian Teori Beras

Selepas pembentangan “Teori Beras” Dr. Braddon itu, beberapa orang tokoh perubatan yang menyokongnya telah membuat beberapa percubaan secara berasingan bagi membuktikan teori terseut:-

1905-1906: Dr. S.H.R. Lucy

“Artikel Dr. Lucy yang bertajuk “beri-beri and Diet” menjelaskan pendirian beliau berhubung teori yang dikemukakan oleh Dr. Braddon. Beliau juga menjalankan percubaan menggunakan beras India di hospital dan penjara di Pulau Pinang dan Seberang Prai selama setahun (dari pertengahan tahun 1905 hingga pertengahan tahun 1906). Hasilnya, beliau merumuskan bahawa beri-beri disebabkan oleh beras Siam.”

1905-1906: Kuala Lumpur Lunatic Asylum

“…Dr. Fletcher turut mengendalikan satu eksperimen di Kuala Lumpur Lunatic Asylum dari 5 Disember 1905 hingga 31 Disember 1906. Berdasarkan keputusan yang diperoleh, beliau menyimpulkan bahawa penggunaan beras Siam, sama ada secara langsung atau tidak, akan menyebabkan beri-beri yang berpunca sama ada daripada racun, kekurangan bahan protein atau kekurangan nilai nutrien yang terkandung dalam beras Siam. Dr. Fletcher kemudiannya membuat eksperimen lanjutan di tempat yang sama dari tahun 1906 hingga awal tahun 1908 yang mengambil masa selama dua tahun 27 hari. Beliau mengesahkan beri-beri sememangnya mempunyai kaitan dengan permakanan.”

Petikan laporan asal: “DURING the year 1905 an epidemic of beri-beri broke out in the Kuala Lumpur Lunatic Asylum. Commencing in, February, it reached its height in July and August, declining somewhat towards the end of December. Out of 219 lunatics treated in the asylum during the year 94 persons were affected, of whom 27 succumbed to the disease. The chief constituent of the rations supplied to the inmates of the asylum was uncured (Siamese) rice, and in view of the fact pointed out by Dr. Braddon that beri-beri occurs chiefly amongst communities with whom such rice is the staple article of diet it was decided, with the sanction of the Government, to place half the lunatics on cured (Indian) rice. The Government readily gave its consent and the experiment was commenced on Dec. 5th, 1905. The result up to Dec. 31st, 1906 (i.e., one year and 26 days) was that 34 out of 120 persons fed on uncured rice suffered from beri-beri and 18 died, whilst among 123 patients dieted on cured rice there were no deaths from beri-beri and only two cases, both of whom were suffering from the disease on their admission to the asylum.” (William Fletcher, District Surgeon, Kuala Lumpur @ The Lancet, 29 June 1907: |"Rice and beri-beri: preliminary report on an experiment conducted in the Kuala Lumpur Insane Asylum").

1907: Eksperimen Durian Tipus

“Pada tahun 1907, Dr. Fraser, Dr. Stanton dan Dr. Braddon melakukan eksperimen menggunakan sekumpulan buruh Jawa untuk menguji hipotesis Dr. Braddon mengenai faktor etiologi beras Siam sebagai penyebab beri-beri. Eksperimen yang dijalankan itu dikenali sebagai Eksperimen Durian Tipus. Kumpulan buruh Jawa tersebut dibahagikan kepada duak kelompok dan setiap satu diberikan sejenis beras yang berbeza iaitu beras Siam dan beras India. Hasil eksperimen menunjukkan beri-beri bukanlah penyakit berjangkit dan penyebab beri-beri didapati dalam beras Siam atau beras putih.”

Dari sumber lain: “In late 1905 evidence in favour of Braddon’s idea of the diet factor grew stronger. An outbreak of beri-beri in the Kuala Lumpur Lunatic Asylum that year, proved to be a testing ground. Inmates who were fed parboiled rice recovered. Dr Henry Fraser, the new IMR Director, received authority to conduct a large scale experiment in Durian Tipis in Negeri Sembilan. Fraser took charge for strict impartiality. 300 Javanese labourers were split into two equal groups. One group was given polished rice and the other given parboiled rice. The results completely vindicated Braddon’s thesis.” (Lim Kean Ghee, 2016: |"THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH IN MALAYSIA", m.s.54).

1908: Dr. J.T. Clarke

“Dr. Clarke telah melakukan eksperimen menggunakan beras India dalam diet pesakit beri-beri di Hospital Batu Gajah, Perak.”

1908: Dr. W.B. Orme

“…Dr. Orme pula melakukan eksperimen yang serupa di Hospital Kampar, Perak.”

(Sumber utama: Noraini Mohamed Hassan @ Sumbu Dunia Melayu: Hubungan Keserumpunan Malaysia-Indonesia, 2017: "Penyelidikan Beri-Beri di Tanah Melayu dan Hindia Belanda, 1880-an Hingga 1914, m.s.278-279).

1907: Penerbitan Teori Beras

Pada tahun 1907, Dr. Braddon berjaya meyakinkan pihak kerajaan untuk menerbitkan “teori beras” secara rasmi, iaitu pernyataan bahawa Beri-Beri adalah disebabkan oleh beras kilang dari Siam dan Burma yang dimakan oleh banduan Penjara Pudu. Ianya diterbitkan sebagai “The Cause and Prevention of Beri-Beri”: “Over more than a decade of observation, experiment and opposition from his fellow medical officers 'Beri-beri Braddon', as Manson dubbed him, had become convinced that the cause of the mysterious disease was associated with one type of rice, imported polished rice. The clinical symptoms of the disease resembled ergot poisoning and in the literature he examined so critically a possible mechanism for the introduction of the poison was suggested - an undetected fungus producing a toxin which poisoned those who ate the rice. … Braddon believed that the pericarp of the red rice (that is, husked but not milled rice) protected the grain from the hypothetical fungus. It is now known that the thiamine (vitamin B^ essential for life is contained in the scutellum, embryo and aleurone layer of the grain. In the case of parboiled or 'cured' rice which is prepared by steeping rice in water and then boiling and drying it, the process actually carries a large fraction of the vitamin from the bran into the endosperm of the seed where it remains even after it is milled. The process facilitates husking but hardens the bran. … Travers objected to his theory on the basis of his observations on three institutions in Selangor - 'a lepers' asylum, a home for incurables, and a criminal prison' - which were supplied with rice from the same store for over six months but only the criminals developed beri-beri. Braddon responded: The explanation here lies in the relative quantity eaten, which is less in the hospitals than in the prison dietary. In the diet of the lepers, as in that of the patients of all hospitals, there is more variety, and fresh meat, eggs or fish are given every day, which is not so in the prison.” (Enid Wylie, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. 61, No. 2 (255) (1988), pp. 93-122: |"THE SEARCH FOR THE CAUSE OF BERIBERI IN THE MALAY PENINSULA"), m.s. 9-17).

1908: Teori Beras Tersasar

Namun begitu, walaupun Dr. Braddon berjaya menemui puncanya, kesimpulan beliau telah tersasar: sangkaan beliau terdapat organisma beracun yang belum diketahui pada beras tersebut yang menjadi puncanya: “Pada tahun yang sama (1907), Dr. W. Fletcher yang memegang jawatan sebagai Patologis Institut Penyelidikan Perubatan turut menjalankan eksperimen di Kuala Lumpur dan memperoleh keputusan yang hampir sama. Selain itu, uji kaji kimia terhadap sampel beras Siam dan beras India turut dilakukan oleh ahli kimia Institut Penyelidikan Perubatan untuk memastikan perbezaan kandungan kimia yang terdapat dalam setiap satu sampel berkenaan. Kajian kimia yang berterusan terhadap sampel-sampel ini meyakinkan penyelidik Institut Penyelidikan Perubatan untuk membuat satu hipotesis iaitu kekurangan nutrien dalam beras adalah penyebab beri-beri dan bukannya racun seperti yang diutarakan oleh Dr. Braddon.” (Noraini Mohamed Hassan @ Sumbu Dunia Melayu: Hubungan Keserumpunan Malaysia-Indonesia, 2017: "Penyelidikan Beri-Beri di Tanah Melayu dan Hindia Belanda, 1880-an Hingga 1914, m.s.279-280).

Akibat kesilapan dalam kesimpulan Dr. Braddon ini, walaupun langkah pencegahannya berjaya, namun kajian selanjutnya membuktikan kesilapannya. Dr. Braddon akhirnya diketepikan dan bersara pada tahun 1908, lalu menjadi peladang di Negeri Sembilan: “On account of this ‘grain intoxication’ theory, further research at the IMR by Fraser and Stanton were led off track and studies failed to find any poison. Braddon himself was sidelined and retired in 1908 to become a planter in Negeri Sembilan.” (Lim Kean Ghee, 2016: |"THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH IN MALAYSIA", m.s.54).

Huraian terperinci kesilapan teori Dr. Braddon: “Dieticians of the late twentieth century would no doubt judge this diet as 'correct' and explain that the 'accessories' would have contained sufficient vitamin B1 to have supported the digestion of the starchy rice to a form useful to the body. There would have been no beri-beri because there would not have been any deficiency of vitamin B1. They would also grant that his belief that the proportion of rice eaten was significant to the extent that the greater the amount of carbohydrate there was to be digested, the greater the amount of vitamin needed to facilitate that process. That is, if the foods supplementing the polished rice contain enough vitamin to allow the rice to be digested, symptoms of beri-beri would not appear. If, however, the polished rice were not supplemented with sufficient vitamin to facilitate the digestion of the normally vitamin-rich grain, symptoms of the disease would appear. … Braddon maintained that 'Those who eat only fresh rice - i.e., the grain newly stripped of its envelopes (husk and pericarp), and not therefore exposed for a long period - escape beri-beri' and as proof pointed to the 'hundreds of thousands of natives throughout Malaya' and other areas who are free of beri-beri. In spite of his knowledge of the different peoples of the peninsula, he had failed to appreciate the difference between the hand-pounded rice eaten by the 'natives' and the product of the steam mills of Rangoon and Siam which was provided for the indentured Chinese labourers.” (Enid Wylie, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. 61, No. 2 (255) (1988), pp. 93-122: |"THE SEARCH FOR THE CAUSE OF BERIBERI IN THE MALAY PENINSULA"), m.s. 9-17).

LATAR PERISTIWA: Dr. William Leonard (W.L.) Braddon (1862-1936).

1901-1912: Peranan Christian Eijkman dll

Sementara itu, kajian yang sama dijalankan di Jakarta, oleh Christian Eijkman. Beliau dan pembantunya Gerrit Grijns berjaya mencapai kesimpulan yang betul, iaitu kekurangan zat pada beras kilang. Zat ini kemudiannya berjaya diasingkan oleh ahli kimia Casimir Funk (diberi nama vitamine, iaitu singkatan 'a vital amine'). Ianya kini dikenali sebagai Vitamin B1: “In the end, it was Christian Eijkman working in Batavia who won the Nobel prize in 1926 for his work on beri-beri. In 1897, Eijkman stumbled on to the cause when chickens in his laboratory fell ill with beri-beri when they were fed polished rice, and recovered when fed unpolished rice. He postulated an ‘anti-beri-beri’ factor acting like an antidote to the disease which he first suspected was caused by some unknown bacteria. His assistant Gerrit Grijns correctly interpreted it as a deficiency syndrome in 1901. Casimir Funk, the chemist, succeeded in isolating the compound from rice bran and called it vitamine in 1912, short for ‘a vital amine’. But he too missed out on the Nobel prize. As the word vitamin became the generic word for all nutrients required in tiny amounts, this vitamin became known first as anuerin, for its anti-neuritic properties and finally thiamine, on account of its sulphur content. Most people know it today as vitamin B1.” (Lim Kean Ghee, 2016: |"THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH IN MALAYSIA", m.s.54).

“Eijkman's breakthrough discovery came after observing sick chickens who were being fed a diet of white rice / KITLV-15344: In the 1890s, as head of the Dokter Djava School in Jakarta, Eijkman’s research found that a certain substance, which he called the ‘anti-beriberi factor’ was present in unpolished rice but disappeared once it was polished, triggering the disease. This substance was later identified as vitamin B12 or thiamine and his discovery changed modern medicine. Rather than being a disease caused by germs spread from one person to another, vitamin deficiency was responsible for the illness.” (Nia Deliana @ Inside Indonesia, Sep 15, 2022: |"Chasing a cure for beriberi").

Perkembangan yang sama menyusul di Tanah Melayu: “The first hint to the cause came from Java, where two Dutch researchers successfully induced a disease similar to beri-beri in fowls by feeding them polished rice. Dr William Leonard Braddon, the Negri Sembilan government surgeon at that time, acted on the lead and concluded with conviction in his 1907 book that the disease was caused by eating polished rice. Although Braddon's publication went on to become one of the classics of Malayan medical research, it was glaringly flawed by assuming that polished rice contained a poison from which other forms of the staple were free of. That misunderstanding was exacerbated when two early researchers at the Pathological Institute made the wrong assumption that beri-beri was an infection caused by germs! Beri-beri only receded into insignificance two years later, when IMR directors Dr Henry Fraser and Dr Thomas Stanton tackled the problem from new experimental angles. They pointed out that the disease was merely caused by thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, and the bran of unpolished rice was rich in that particular form of vitamin B.” (Alan Teh Leam Seng @ New Straits Times, June 16 2021: |"Malaya led the way in medical research").

1910: Hasil Langkah Pencegahan

“Penggunaan beras India dalam kalangan pesakit beri-beri di hospital dimulakan seawal tahun 1902 di Negeri Sembilan. Langkah ini kemudiannya diikuti oleh tenaga perubatan di Pahang pada tahun 1906, di Perak pada tahun 1908 manakala di Selangor pula pada tahun berikutnya. Pada tahun 1910, kematian akibat penyakit beri-beri mencatatkan rekod paling rendah dalam tempoh 32 tahun (1883-1914) iaitu 11.2 peratus. Dr. G.D. Freer, Pegawai Perubatan Kanan Selangor melihat kemungkinan in pada penggunaan beras India. Keberkesanan penggunaan beras ini turut diakui di Singapura. … Pada awal tahun 1910, Dr. Fraser dan Dr. Stanton membuat kesimpulan tentang punca beri-beri. Penyakit ini dikesan akibat kekurangan nutrien dalam beras putih yang dimesin. Kesimpulan tersebut memperkukuh hasil eksperimen awal yang mereka lakukan pada tahun 1907. Salinan laporan bertajuk “On the Etiology of Beri-beri” diajukan kepada kerajaan India, kerajaan Burma, Setiausaha Kolonial Sri Lanka dan Setiausaha Kolonial Hong Kong serta Jawatankuasa Penasihat Tabung Penyelidikan Penyakit-penyakit Tropika.” (Noraini Mohamed Hassan @ Sumbu Dunia Melayu: Hubungan Keserumpunan Malaysia-Indonesia, 2017: "Penyelidikan Beri-Beri di Tanah Melayu dan Hindia Belanda, 1880-an Hingga 1914, m.s.279-280).

Huraian punca kekurangan vitamin B1 pada beras kilang: “The preparation of the 'higher quality' white polished rice from Burma and Siam was a much more complex mechanical procedure. … In the mills the rice is first sifted and winnowed mechanically to remove any impurities and then husked by being forced between discs coated with emery and cement, causing the hull to split. The grain is then scoured to remove the waxy outer bran layers. A truncated inverted cone of cast iron covered in emery and cement which revolves at high speed within a steel wire mesh is used to rub off the brain. The process is repeated several times and is followed by the polishing process which consists of passing the rice through several revolving rollers covered with sheepskin or buffalo hide. This removes the innermost (aleurone) layer and any floury particles from the grain leaving it smooth or polished. This type of milling would certainly remove any felt-like fungus such as that described by Guerin but it also removes much of the nutritive value of the rice leaving only the starchy endosperm. A study by Rosedale showed losses to be 29% of the original protein, 79% of the fat, 84% of the lime and 67% of the iron. Essential vitamins, the existence of which was beginning to be suspected when Braddon wrote his book, were also found to be lost in milling and polishing because they are mainly stored in the outer layers of the grain. A study by Hinton found that the distribution of thiamine (vitamin Bi ) in red rice was 50% in the scutellum, 33% in the aleurone layer, 9.7% in the embryo and 6.3% in the endosperm of the grain. (See Diagram 1). In addition to the loss of protein, fat, valuable minerals and vitamin Bx , other vitamins are also lost. Kik and Williams found the average losses in thirteen varieties of rice to be 76% of the thiamine, 56% of the riboflavin and 63% of the niacin.” (Enid Wylie, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. 61, No. 2 (255) (1988), pp. 93-122: |"THE SEARCH FOR THE CAUSE OF BERIBERI IN THE MALAY PENINSULA"), m.s. 9-17).

| Laman Utama | Hubungi Kami | ||||||||

| Siri Cebisan Sejarah: | Bangi | Gambang | Hutan | Ipoh | Kajang | Kuala Lumpur | Kuantan | Pulau Pinang | Hubungi Kami |